Your Cart is Empty

FREE standard shipping to the continental US.

FREE standard shipping to the continental US.

FREE standard shipping to the continental US.

Designed and executed expressly for the Columbian Exposition of 1893, these extraordinary and unique compotes are sterling silver with original all-over gilding. Each supports a fine ruby cut to clear glass basket cut with fine neoclassical decoration. These baskets sit in fitted rings with attached cast laurel wreaths. Four fluted columns rise from the cast square platform base which stands on four scrolling feet, each bearing a boldly cast winged griffin. Classical details of acanthus and anthemia, scrolling volutes and arabesques, laurel and wreaths abound throughout the design.

Nearly every piece is cast with hand chased detail. Creating the molds for casting is the most expensive process in the making of silver and since the cost could not be amortized over a large production, these pieces were extremely expensive to make. Gorham records indicate that each compote took 26 hours of casting (this does not include the creation of the molds) and 168 hours of chasing to finish the casting. The factory cost of these compotes was $300 each, with a presumed retail price between $500-600 each(1). This was a very significant sum during a period when a highly skilled and well-paid silver chaser might earn $15-20 a week.

These exceptional pieces measure 8 inches high by 9 3/4 inches in diameter. They are in outstanding condition, have never been monogrammed and weigh a combined 93.8 troy ounces. Each is marked 'STERLING', the special order number 'S1021' and with Gorham's trademark and date code.

Gorham's records indicate that this pair of dessert stands was part of a larger dessert service which included a plateau, an epergne, two smaller compotes and six candlesticks.(2) These two compotes are the only known survivors of this service.(3) Gorham had a documented relationship with glass maker H. G. Hawkes, of Corning New York. These custom ordered glass bowl inserts are not signed, but Hawkes or Sinclair seem the most likely makers.

Not only did Gorham win an award for their gilt silver at the Columbian Exposition (see below for details), The New York Times wrote about this service both times it covered Gorham's exhibit at the fair.

When discussing Gorham's gilt silver at the World's Columbian Exposition, The New York Times stated on September 20, 1893:

It [Gorham's gilt silver] illustrates…American silversmiths can also do the highest class of European work. In a gilded dessert set with plateau, the very highest type of this work is shown. The set is correct Louis XVI in design, and the dishes are beautiful examples of cut ruby glass.(4)

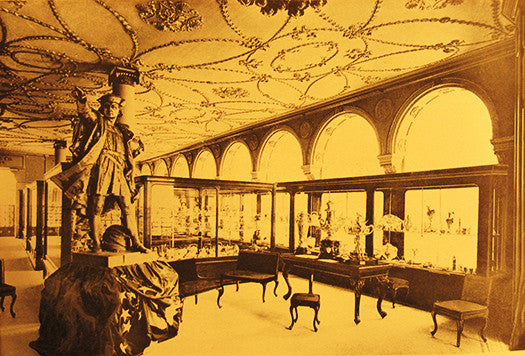

In early 1894 after the close of the Columbian Exposition, Gorham organized a special exhibit of custom pieces from the fair at their New York store on Broadway at 19th Street. According to The New York Times, the dessert service was shown on a table by the entrance: 'Everything in the room is of the most artistic design.'(5)

The importance that managers at Gorham placed on the dessert service is evidenced by their record keeping. Records for the service are not kept with other special order records, but in volume 36, which selectively includes only the very best pieces produced by the company between 1889 and 1907. In fact, the compotes are listed on the same page as the 'Nautilus Centerpiece' (see below), now in the collection of the Dallas Museum of Art.(6)

Gorham's outstanding skill at casting was on display for all to see at the Columbian World's Fair – the life sized statue of Columbus was one of the most talked about pieces of silver at the fair. Made from 30,000 ounces of silver (one full ton)(7), it was a technical and artistic triumph. The statue dominated the Gorham display. As The New York Times noted about silver at the Columbian Exposition, '…America unquestionably takes first rank, 'and felt specifically of, 'The Gorham Company as representative of this high development in silversmithing.'(8)

During the 19th century, international expositions, or world's fairs, became the most prestigious marketing avenue for luxury retailers. Companies would invest exceptional resources to create their displays. These expositions became the equivalent of selling to royalty during an earlier era: only the very best would do. The publicity surrounding the fair could make, or break, a firm's reputation.

Many of the objects on show were prohibitively expensive to all except the very wealthiest clients. Companies took significant financial risk making these masterpieces. Gorham's Nautilus Centerpiece made for the Columbian Exposition did not sell until 1921, 28 years later.(9)

The 1893 Columbian World's Fair was truly spectacular. To celebrate the 400th anniversary of Columbus finding the new world, an entire city was built on the shores of Lake Michigan in Chicago. It covered 686 acres and included 300 specially constructed buildings.(10)

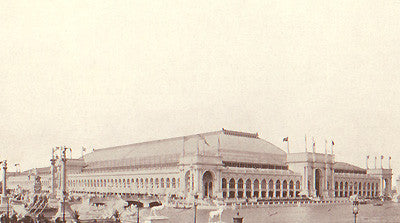

The Grand Court of Honor at the World's Columbian Fair 1893

The Grand Court of Honor at the World's Columbian Fair 1893Chicago architect Daniel Burnham managed the physical construction and maintenance of the facilities. A committee of leading architects involved with the fair including Burnham, Stanford White, Richard Morris Hunt, Louis Sullivan (assisted by a young Frank Lloyd Wright), Frederic Law Olmstead and others chose the theme of classicism to be the signature of the architecture at the fair. Built as a temporary facility, the buildings were constructed in composite materials meant to resemble white marble. The huge park became known as 'The White City.'

During the six months it was open in 1893 there were 27.5 million visitors(11) to the fair, a particularly amazing number in light of the fact that the US census counted 63 million Americans in 1890. Considering that it occurred during a severe economic contraction made it an even greater success.

So successful was the Exposition that it began a massive classical revival at the turn of the century. The most lasting example can be seen today in Washington, D.C. where many federal buildings were built after the fair in the classical style – a permanent 'white city'. (In fact, Burnham worked in Washington, D.C., too: Union Station is his 1903 design. New York's 'Flat Iron Building', generally considered the first 'skyscraper', is also Burnham's design.)

The Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building -

The Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building - The Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building, where Gorham's exhibit was center stage, was the largest building constructed to date. Three times the size of St. Peter's in Rome, it covered 31 acres with the roof rising 245 feet with no supporting columns in the center.(12) The central hall could 'comfortably' seat 50,000(13) and 150,000 people crowded in on opening day.(14) Gorham's exhibit, next to Tiffany's, was under the central dome where murals by J. Alden Weir displayed the 'Goldsmith's Art'.(15)

In the gold and silverware category, Gorham dominated the exposition. Winning 30 awards, they earned twice the number of prizes of their nearest competitor, Tiffany & Co. who won 15. Included in Gorham's awards were prizes for gilt silver, silver mounted cut glass and crystal, and 'artistic display of exhibit as a whole.'(16) The Royal Museum in Berlin purchased several objects from Gorham at the fair.(17)

The New York Times and other observers noticed Gorham's achievement at the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893. The Gorham designers, directed by William Codman and Antoine Heller, led a group of virtuoso artisans crafting an exhibit that impressed all. The French Government, in their report on the Columbian Exposition, compared Gorham to Tiffany and noted that Gorham, 'is able to produce artistic and decorative work, calling for the highest skilled and careful hand labor.'(18)

By all accounts, Gorham's exhibit at the World's Columbian Exposition was a stunning success. Gorham had met the challenge of the international exhibition and it would be only a few years before they were generally acknowledged to be the leading silversmithing firm in the world. These dessert stands, and the service they came from, were admired far and wide and helped develop Gorham's future world class reputation.

Exhibition: World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893.

Endnotes:

Sign up to get the latest updates and current musings in our occasional newsletter…