Your Cart is Empty

FREE standard shipping to the continental US.

FREE standard shipping to the continental US.

FREE standard shipping to the continental US.

July 15, 2017 2 min read

John C. Moore is know today as the great silversmith who worked exclusively for Charles Tiffany and Tiffany & Co. after 1851. His son, Edward, would run the silver department at Tiffany's during the era of it's greatest creativity.

Moore first gained fame for pieces, sold through the important jeweler Ball, Black & Co., that were made in the rococo revival style, then called the 'French' style. His most famous work from this period is the Collins tea service, made of solid gold, that was displayed at the 1851 and 1853 World's Fairs to great acclaim.

His flatware is relatively unknown. Likely, Tiffany had him specialize in holloware because Tiffany procured flatware from other silversmiths, such as John Polhamus and Henry Hebbard. Both these smiths may have been more productive and hence less expensive due to their specialization in flatware.

However, before joining Tiffany, John C. Moore was the second American silversmith (after Michael Gibney) to patent silver flatware designs. Gibney received the first and second silver flatware design patents, numbers 26 (name unknown in 1844) and 59 (Tuscan in 1846).

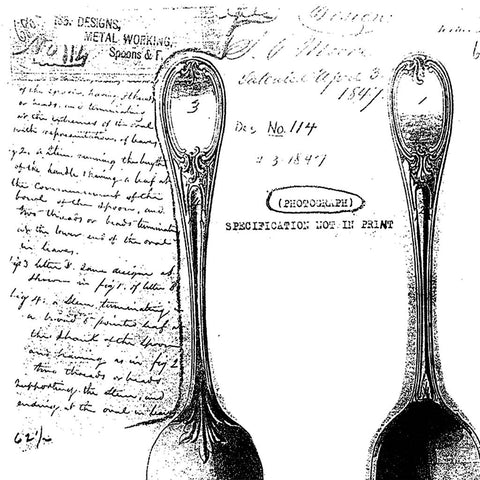

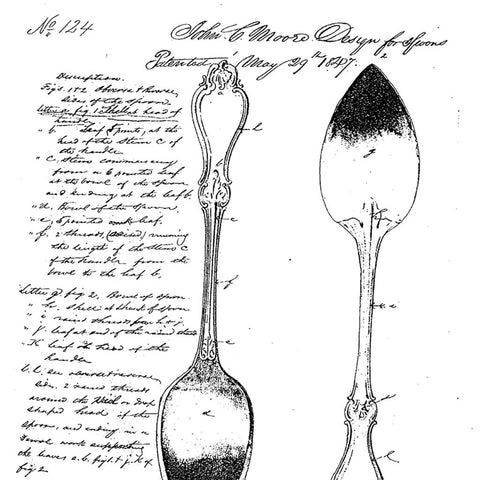

In April and May of 1847, Moore received patent numbers 114 (Louis XIV) and 124 (pattern name unknown). It wasn't until May of 1849 that William H. Lewis became the third silversmith to be granted a design patent for flatware.

The patent above is known today as John Polhamus' Louis XIV pattern and was designed in the rococo or 'French' style with scrolls and foliate embellishments. Moore must have sold the rights and dies to Polhamus, possibly in tandem with his agreement to work exclusively for Tiffany.

Patent number 124 is described in the patent application as having a 'shell' ornament at the top of the handle. While the name of this pattern is unknown and it resembles the then popular Prince Albert pattern, the shell design clearly refers to the 'rocaille' (French for 'shell') or rococo decoration popular in France during the 2nd quarter of the 18th century.

Moore decided to tie his fortunes to the emerging 'French' style designs of the rococo revival in both holloware and flatware. He was even an early adapter of French forms for the American market, as can be seen in this adaptation of a French 'sucrier'.

This wise business decision by Moore (possibly helped by his son Edward) put him in the position to become the leading silversmith of his generation. The rest is history.

Sign up to get the latest updates and current musings in our occasional newsletter…